August 20th, 1977

One day in October 2016, I arrived at Yangon’s Mingaladon International Airport and took a taxi to my downtown destination. While driving down Pyay Road with its brightly illuminated, glittering facades, high rises, and new flyovers, it crossed my mind how it was when I landed in Rangoon back in 1977.

In those days, there was one daily flight from Bangkok to Rangoon, operated by Thai Airlines, and occasionally additional ones by Burma Airways. Today, dozens of international flights land and take off from Mingaladon daily.

Flashback: It’s 7:30 at night, August 20th, 1977, in Rangoon, Burma. I’m riding in a light blue Buick Super 51 Sedan with dim beam lights (built in 1946), dashing through Burma’s capital, Rangoon. The old banger is rattling and squealing all over. But that doesn’t seem to bother the driver at all. Nor the fact that the windows are ratcheted only halfway up, and water is pouring in. The old boneshaker is on its way from the airport to downtown. It’s pitch-dark and pissing rain heavily. Sometimes, there’s a flash on the roadside: a neon lamp, a candle, or an electric bulb. Occasionally, a car approaches, or we splash a passing rickshaw. Aboard are three hippies, including me, the chronicler. And we wonder: Rangoon is supposed to be a city of two million people. However, we haven’t seen a single soul since we left the airport! What’s going on here? Where are the millions? The driver is an Indian who introduced himself as One-Eyed Joe. He’s a fat, scruffy man wearing a sarong, flip-flops, and an undershirt soaked in sweat.

Since we boarded his sorry transport, he’s been trying to talk us into selling our treasures at a bargain price: three bottles of Johnny Walker Red Label and three cartons of Triple Five cigarettes. We fob him off with a knowing smile – we’ve heard about this scam before. Tomorrow, we’ll get twice as much for it. Besides, we already have Burmese money. We bought some from a money changer at 20 Kyat in Penang for one dollar. Three times the official rate!

Since we boarded his sorry transport, he’s been trying to talk us into selling our treasures at a bargain price: three bottles of Johnny Walker Red Label and three cartons of Triple Five cigarettes. We fob him off with a knowing smile – we’ve heard about this scam before. Tomorrow, we’ll get twice as much for it. Besides, we already have Burmese money. In Penang, we bought some from a money changer at a rate of 20 Kyat for one dollar. Three times the official rate!

Finally, we arrived at the Thamada Hotel, among the best of the seven hotels with a license to accommodate foreigners. We found it a little run-down. Later, we realized that it would be the highlight of our trip; we were about to see much worse. We submitted our passports and money forms and checked in. Our rooms were modest – but with air conditioning. Rangoon’s dining scene was relatively straightforward: besides the hotel restaurants, only two were considered “safe” by the small expat community: Red Ruby on Bo Aung Kyaw Street and Burma Kitchen on Shwegondine Road. Both have survived to this day. The first is still under its old name; the other was converted into a Japanese restaurant (Furusato) long ago. So, we chose the hotel’s restaurant on the first floor.

It was here that I first saw the menu that was identical to all government hotels in Myanmar. It would become a trusted companion during my travels in Burma. Rangoon was the only place where one could get lobster Thermidor. The waiter was surprisingly well-dressed: he wore black trousers, his cleanest dirty white shirt, and a bow tie. Noblesse oblige! He was even sporting a pair of black shoes. The ambiance reminded me of a visit to East Berlin. He served our dinner most professionally. I was especially impressed by how he balanced the peas from the platter onto my plate. For a long time, I couldn’t help but feel that Burma was some kind of tropical East Germany. And I loved it! After dinner, we returned to our rooms, and while in bed, I reviewed the day’s events. And quite one it had been!

It started in Bangkok, Thailand, at dawn after a short but lively night. I was lying in bed in my room at the ATLANTA Hotel with my Thai girlfriend named Nit when suddenly someone knocked violently at the door: ‘Open up! Police!’ I wrapped one of the worn-out Atlanta towels around my hips and opened the door. Two Thai coppers pushed me aside and entered the room. They ignored the girl sitting fearfully against the bed’s backboard, blanket up to her nose. They lifted the mattress but didn’t seem interested in a bundle of traveler’s checks I had reported stolen the day before. In my mind’s eye, I saw myself in jail, the notorious Bangkok Hilton (see photo). To my relief, they lowered the mattress without saying a word. Then they searched my luggage and looked around before they left the room. Only a drug bust! Lucky me! After escaping the fright, we fell asleep again. At 9 a.m., we went for breakfast in the hotel’s cafeteria.

Our flight to Rangoon was scheduled for the late afternoon. So, we spent our time at the hotel’s swimming pool. Then, we (my friend Uwe, a Belgian guy named Philippe, and myself) boarded public air-con bus no. 11 to Bangkok’s Don Muang airport. We had booked a Burma Airways flight from Bangkok to Kathmandu with a stopover in Rangoon. Other travelers had told us about the whisky-and-cigarette business. So, every one of us bought a bottle of Johnny Walker Red Label and a carton of 555 cigarettes.

These items were extremely popular in Burma. According to rumors, one could finance a complete week in Burma from the proceeds, except for hotels and flight tickets. Burma Airways plane did not exactly inspire confidence – an old Fokker Friendship, only capable of transporting 52 passengers. When we tried to store our hand luggage in the overhead compartments, we were in for a surprise: no space! All were filled up to the rim with Johnny Walker and 555 cartons.

The flight attendant asked us to store our things under the seat. Especially as it was only a short flight, a little more than one hour. They even offered a meal: every passenger got a white box. When I opened it, an enormous cockroach crawled out of it. Hard to believe, but true. However, the cake was wrapped in plastic, so I ate it. The orange was okay, as well. When we arrived, it was raining heavily. Workers holding umbrellas escorted us to the immigration counter. The airport was rather small, and we were processed relatively quickly.

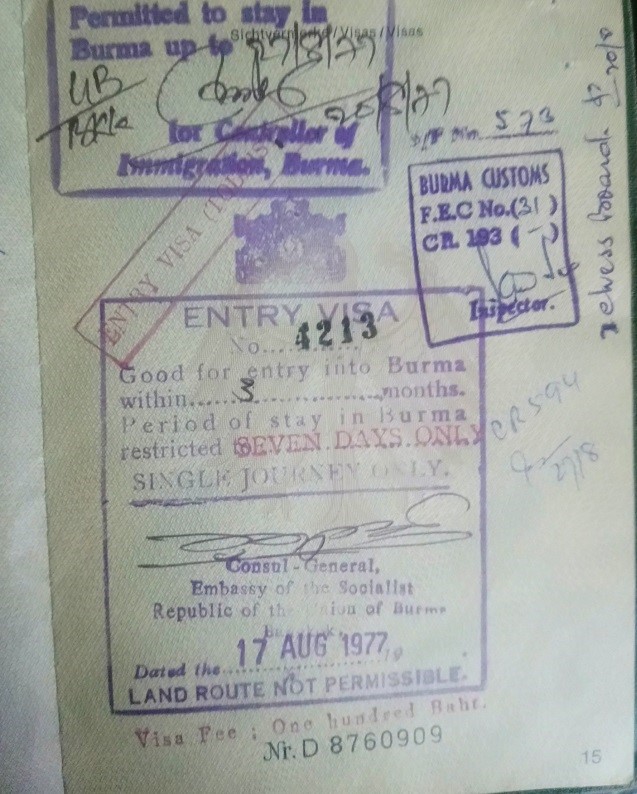

The most challenging thing was the completion of the ‘form’. We had to register all foreign currency in our possession. Whenever we spent money (tickets, hotels), we had to enter it in this form and convert it into Kyat, the national currency. If one didn’t have enough money on his record, he had to change money again. It wasn’t straightforward, and it reminded me of East Germany. There were quite a few parallels with the communist state. But contrary to the GDR, the people here were of overwhelming friendliness. When we stepped out of the arrival hall, we were overrun by hordes of touts and taxi drivers who wanted to take us to our hotel at exaggerated prices. Hey, find yourself another fool! We bargained One-Eyed-Joe down to one dollar, and off we went!

Before our first visit to Burma, we hardly knew where we were going. In those days, the country was even more unknown today. Twenty thousand foreigners (and only a fraction of them were tourists) visited the country in 1977. Many potential tourists were probably put off because they could stay only one week. For us, it was okay, as it was just a stopover on our way from Bangkok to Kathmandu. Little did I know that it would be a life-changer for me. My friend Uwe and I had covered about half the distance of our great trip from Bali to Sri Lanka (most of it overland).

The following day, we had breakfast at the hotel’s cafeteria. Afterward, we took a stroll through Rangoon’s downtown. We got rid of our goodies in no time – a 300 % profit – not bad! These items were indeed status symbols! We saw them in many places next to family photos and bric-a-brac. When the bottle was empty, it would be refilled with tea to keep up the good impression. They were also used as a semi-official measure of capacity, e. g. for gasoline. In some places, they are still in use. One-Eyed Joe had told us that visiting the May Hla Mu pagoda in North Okkalapa was essential for every tourist. A highlight, if there ever was one! Good for his wallet, too. It felt like a jungle excursion. In the afternoon, we toured Shwedagon Pagoda in the rain.

There were hardly any cars on the city’s wide roads. We saw only old US street cruisers or British Austin limousines. Plus, a few locally-made vehicles. The blue ones had four wheels and resembled East German Trabant cars. The three-wheelers looked like a 1950s West German Borgward Goliath. To our surprise, we saw no motorbikes or even bicycles. Later, we were told that those were banned in Rangoon. The buses were a gas! Bedford and Chevrolets from the 1930’s! We could not read their destinations as it was all in pretzel script. And the weirdest thing: the passengers were traveling in these vintage cars as if it was the most normal thing in the world! Until then, I’d considered them more like a fairground attraction.

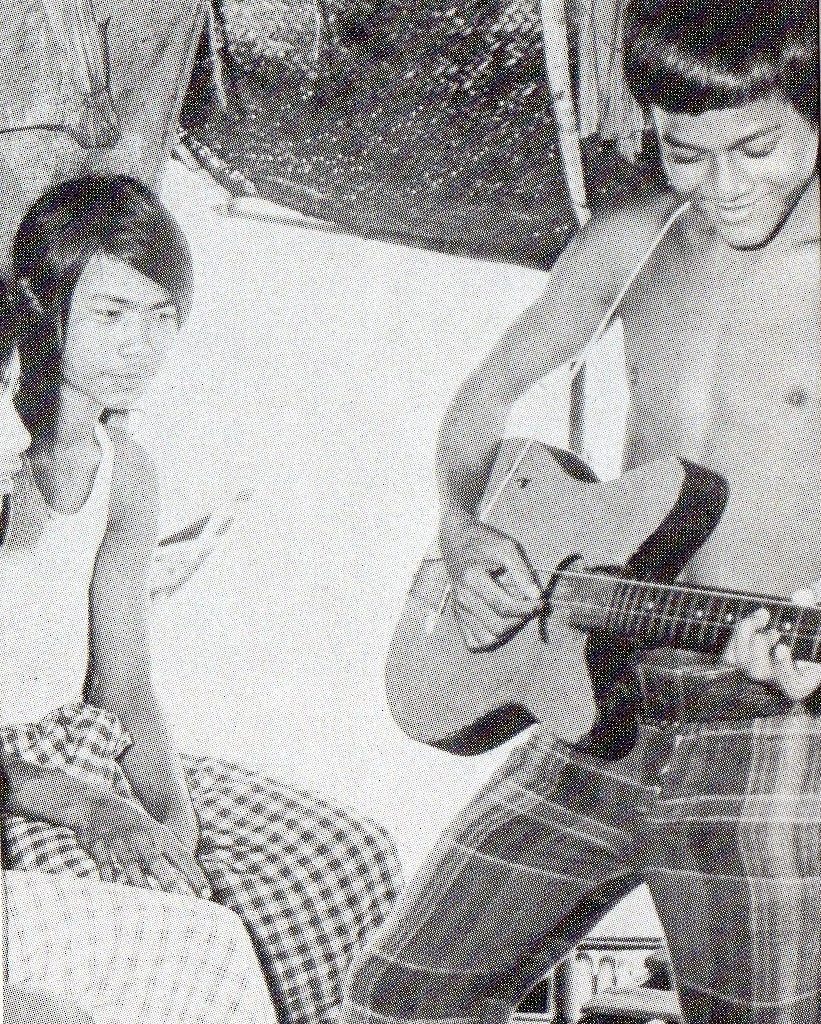

In the evening, we visited Tourist Burma at Sule Pagoda and bought tickets for the train to Mandalay the next day. We concluded our first day in Rangoon by strolling through the alleys near Sule. It was a magical atmosphere: teenagers sat in the streets singing with guitar accompaniment. They gave us a big hello and an even bigger smile when we walked past. It seemed that foreigners were a curiosity here in Rangoon. Ground floor dwellers sat in their flats with no street walls but only shutters. So, we had a chance to see how the people in Rangoon lived. And still no cars in sight. And suddenly we saw them – they were parked inside the apartments! We’d been wondering for quite some time why there were ramps leading from the streets into the houses. As it seemed, wheels represented an enormous value in Burma and had to be protected against thieves at any cost. And so, the people were sitting behind bars by the lights of their neon lamps and candles, listening to the radio, chatting – or maybe admiring their rolling treasures. Television didn’t exist in Burma in those days. It was introduced only ten years after my first visit. It was evident that the people of Rangoon had an urgent need for security. Not only were ground-floor flats secured with iron shutters, but even the windows on the third floor were heavily secured. And this hasn’t changed in more than forty years! Burma seemed to be a dangerous place.

The train to Mandalay departed at 6 AM. Rangoon’s central railway station looked like it was time-warped from the 1930’s. It was dark, and people were lying on the platforms, many wrapped in blankets. We were unsure if they were waiting for their train or had nowhere to stay. I had entrusted my attaché case to the hotel’s store room. It was a bit of a disappointment when a diesel engine dragged the train into the station. I’d have preferred (and expected) a steam engine. Vast swathes of countryside were submerged in water. In some places, the track was invisible for miles. But the engine driver seemed to know his way. And it was great fun!

We arrived in Mandalay at around 10 PM. Much to our surprise, we were ‘welcomed’ by the staff of ‘Toyota-Express.’ These people organized trips for hippies in Upper Burma. Up to ten passengers were squeezed into the back of a Toyota pickup truck, their luggage on the roof. Only sissies would pay more for the right to sit in the driver’s cab. Mandalay-Bagan-Inle-Mandalay in four days. Not for the faint-hearted. And it’s not recommended. Instead, we followed a tout to a dump called Mann Shwe Myo (Mandalay Golden City).

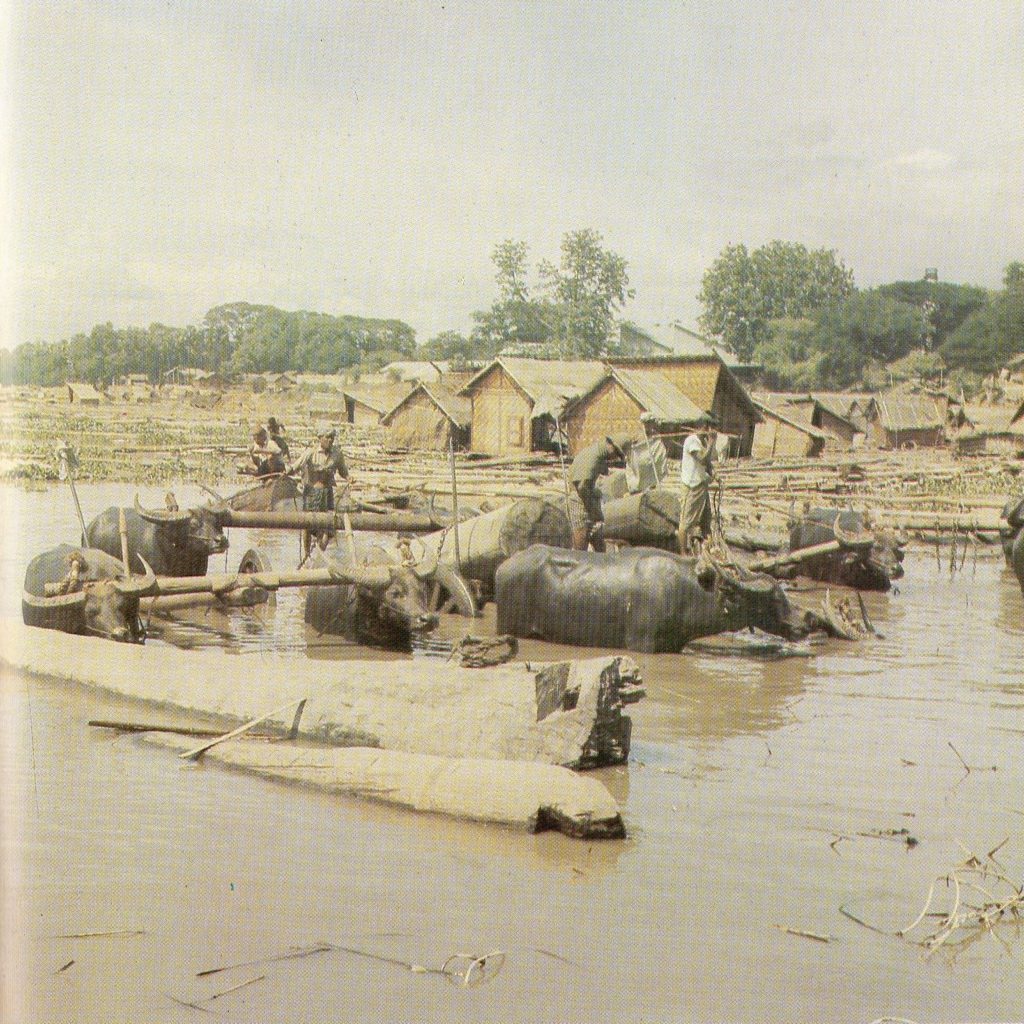

The next day, we went sightseeing and saw the usual attractions; Mandalay Hill, with the giant guardian lions, made a lasting impression. If I’m not mistaken, we also visited the Mahamuni-Buddha. But I don’t remember it. Our favorite was the Irrawaddy Riverside. A pile village in front of the levee teemed with life. The absolute highlight was a place called Kywe Zun, where gangs of water buffaloes pulled heavy teak logs out of the river and up the levee. Some old trucks were in action, too. If they couldn’t make it up the levee alone, a few water buffaloes were harnessed with yokes and iron chains, and they made all the difference. A remarkable sight was the children on the levee. They were very friendly, and whenever they saw a foreigner, they made the V-sign with their fingers and shouted:’ Peace, peace.’ No idea what that meant. Most probably, it had been introduced by some hippies.

From Mandalay we flew to Bagan. We stayed at the Moe Moe guest house – only three dollars a night. In those days, the village was located inside the old city walls and had a charming atmosphere. In 1990, the inhabitants were forced to relocate; the village of New Bagan was built around 5 km downriver. The villagers weren’t happy with that, and there was an outcry even in the international press. However, I have to put something straight here: Those people who live in big new houses in the new town nowadays and still cry over the loss of their old village seem to have forgotten what it looked like and how they lived before. Most dwelled in shabby little houses – many built with bamboo mats. The plots were small, and the people were poor. Today, New Bagan must be one of the wealthiest villages in the country. It was declared a tourism zone, and the villagers were given big plots of land. Many sold them for a fortune to people who wanted to build hotels or restaurants. My friend Aye Thwin was one of the few villagers who admitted that the forced removal was a blessing in disguise.

Two years before our visit, a devastating earthquake had struck the plain of Bagan. The ancient city looked like a giant construction site – it was staggering! We rented a horse cart and drove from temple to temple. In those days, it was still permitted to climb up the structures – absolutely No Go nowadays. Thatbyinnyu, the tallest temple, offered the best view. I will never forget the sunsets I watched from its top. With some luck, skill, and a little tea money, we got flight tickets from Bagan to Rangoon. Burma fascinated me, and vowed that this would not be my last visit there. But little did I know that it would take me only three months to be back!