A train ride to Mandalay in the 1950's

Hi folks, it’s never been easy for travelers on Burma’s trains. I remember traveling from Rangoon to Mandalay and back quite a few times in the 1970s and 80’s. It was an agonizing ride which took – and still takes! – 16 hours. If you were lucky … I always preferred the day trains as – at least according to the railway officials – sleepers didn’t exist. Which was a blatant lie. In fact they were reserved for the military as I learned soon enough. Nevertheless it was the most comfortable way of long-distance travel next to flying. Today’s luxury buses didn’t exist and the roads were in a sorry state of disrepair. So everybody tried to go by train.Tourists were

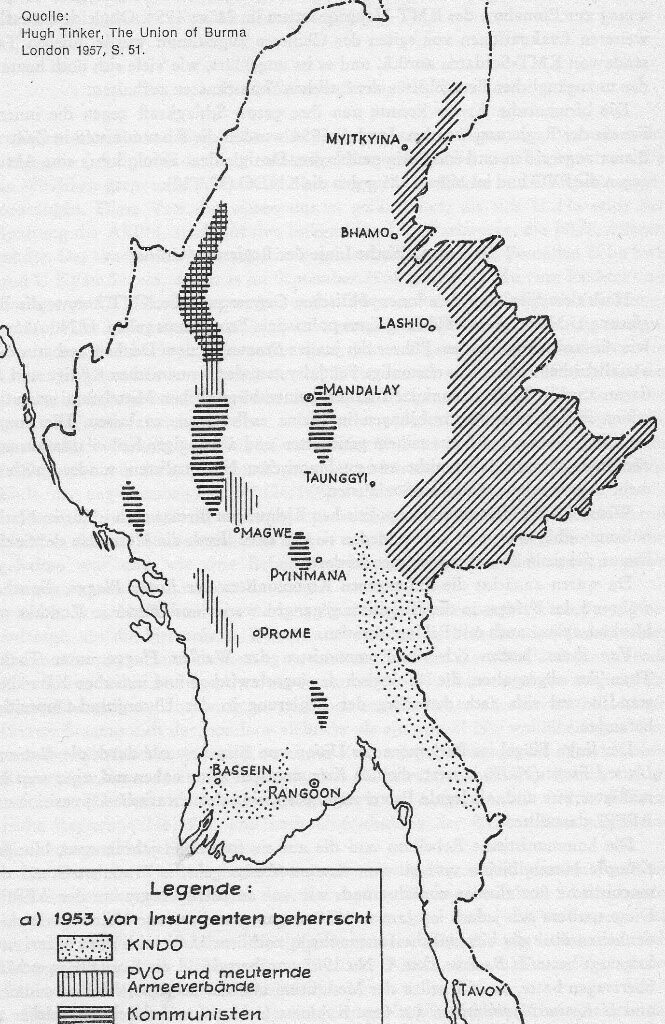

somewhat privileged as Tourist Burma was given priority because their clients had to pay several times more than locals. Nevertheless, it was never easy to get train tickets and I remember bribing the man in charge with a Playboy Magazine or other goodies. In the 1950’s and 60’s it was even worse, as Norman Lewis (Golden Earth) and Claude Moisy (Birma) reported. The latter had to change from trains to buses and back several times during his trip from Rangoon to Moulmein because the track had been bombed by insurgents. However, compared to what Harry Hpone Thant has to tell in the following story, tourists traveled in comfort.

On The Road to Mandalay

No, this is not about taking the luxury tourist boat “Road To Mandalay”. This is about my first experience on a train in Burma. I was in the 5th grade, around the 2nd half of the 1950s, when I first rode on a train. My family was going on a pilgrimage to Mandalay and we went by train. But it was not that easy during those times to travel by train to anywhere in Myanmar. The civil war had abated somewhat, but there were still instances of tracks being mined or shot at by insurgents.

My dad had ordered some of his staff to go to the coach assembly yard, opposite the row of cinemas on Bogyoke Aung San Road, in the evening to block our seats in one of the coaches so that we could get them on the morning train. I was so excited to travel outside of Yangon for the 1st time. The whole family was burdened down with baggage; sleeping bags, aluminum food carriers, water jugs, thermos flasks etc. Most trains in those times did not have restaurant cars, so we took along food: boiled rice, fried chicken, fried fish, fried spicy fish paste, bread etc. Coffee was in thermos flasks. Some mandarin oranges for snacks. And as there was no bottled water available in those times, a big aluminum water jug as well.

The long row of coaches inched into the station. The passengers stirred, getting ready to board. But the coaches were already full! Seemed like other passengers had had the same idea and occupied the seats last night. Anyway, we jostled inside. I cannot remember how I got in. What I remember is that my stout aunt had to be pushed through the window as she couldn’t get through the doors because of the crowd.

So, toot, toot and we were on the way. The engine was a big black steam brute, puffing out black smoke and steam. Panoramic scenes flashed by outside. I was mesmerised. Mom told me to put on my sunglasses. “Coal dust would get into your eyes”, she warned. “Put on your hat. Your hair will be covered in coal dust”. No, I was too excited to heed her warnings. The result was that my hair was jammed solid by evening time.

In those days, trains did not go from Rangoon to Mandalay directly. All passenger trains on this route made a night stop at Pyinmana, about half the way to Mandalay. Between Bago and Pyinmana, the tracks ran close to the Bago Yoma (Bago Mountain Range) which was a stronghold of the insurgent Burma Communist Party. The insurgents would sometimes come down the mountains to lay mines on the tracks during the night or ambush trains. There was one very ugly incident, in 1951 I think, when a group of ethnic insurgents blew up a train, kidnapped a number of young female students coming back for the new academic year at Rangoon University and exchanged them for arms and ammunition with the Chinese KMT insurgent Army on the Thai border. So the trains tried to run this gauntlet during the daylight hours and stayed overnight at Pyinmana.

Along the way I saw some steam engines parked on the adjoining tracks. They had big, heavy iron girders and other assorted junk on the flatbed cars in front of the engines. Dad told me those were armed escort trains, used to patrol the tracks and the heavy flatbed cars in front were to make the mines detonate. Anyway, being a small boy, I was not overly worried nor did I understand his explanation. Then there were also huge contraptions beside the tracks, dripping water. Dad explained that these were water fountains for the steam locomotives to refill their water tanks. But all I saw was boys about my age playing under the dripping water. There were also abandoned freight cars by the side with families living inside. They were lowly paid railway workers lacking funds to rent out living quarters in town. So they used these freight cars as temporary accommodation, according to my Dad.

We arrived at Pyinmana just after dusk. As the train slowed down, I saw young boys and girls my age run beside the coaches shouting, “Pure, cool drinking water, pure, cool drinking water”. They balanced earthen pots on their heads. Some of these water sellers were grown-ups. There were even some old people selling hot green tea from earthen teapots. I was quite young then and was not able to appreciate their hard life nor understand their struggle for survival.

As Pyinmana was a transit station I was sure there would be many food stalls. But I did not get a chance to see them. Mom fed me with what we had brought from home. Like most Myanmar ladies of that time, women folk did not go to food stalls to eat, only men. So my mom, my aunts and I shared our dinner between us.

There was a wash-room, too, in the Pyinmana Railways Yard. All patrons were provided with a barrel of water and soap. The barrels, as most of us would remember, were discarded 50 gallons oil drums, the ones with two raised belts around them. Mom took me to one enclosure and washed my hair and the grime from my blackened face. I think the owners of these wash-rooms charged some fees.

Men folk usually hired folding beds to spend the night. The beds had scissor-like legs with the two sides joined with a hemp cloth, usually a piece of gunny bag. The legs were opened to set up the bed and one slept on this hemp cloth. We called them Indian folding beds and you won’t seem them anymore nowadays. But the mosquitoes, the mosquitoes!! My mom and all the women folk of course slept inside the coaches but these pests, buzzing around our heads made it really difficult to get a sound night of sleep even for a young boy like me. As the sun rose in the East, our train stirred up with humanity and soon it was chugging away on its journey to Mandalay.