The Burmese script

Harry recently contributed a very interesting article about the literacy campaign in the seventies and eighties in our Old Burma Hand group. It came as a bit of a surprise to me as Burma was always considered as a developing country with a high literacy rate. Early European travellers in Burma (16. Century A.D.) were rather surprised that many Burmese (even women!) were literate. Quite contrary to Europe where only a fraction of the population knew how to read and write. Of course, this achievement was the result of monastic education.

Now let me tell you about my encounter with the Burmese script. When I started to write my PhD thesis about Burmese puppetry in the early 90s it quickly became clear to me that I would have to learn the language – or at least try it. My focus was on learning the script as I needed to attach a glossary. Those days it was not easy to study Burmese in Germany. It’s even more difficult nowadays, as I understand. ‘Fortunately’ the Berlin wall had just come down and so I was able to enrol in a Burmese class at Humboldt University in formerly East Berlin. As we all know, it’s difficult to teach an old dog (I was 42 years old then) new tricks and it would be an exaggeration to claim that I can speak Burmese. But I’m able to help myself in a simple conversation. And I know the basics of reading and writing. Among others, we used a textbook for the literacy campaign mentioned by Harry (see photo).

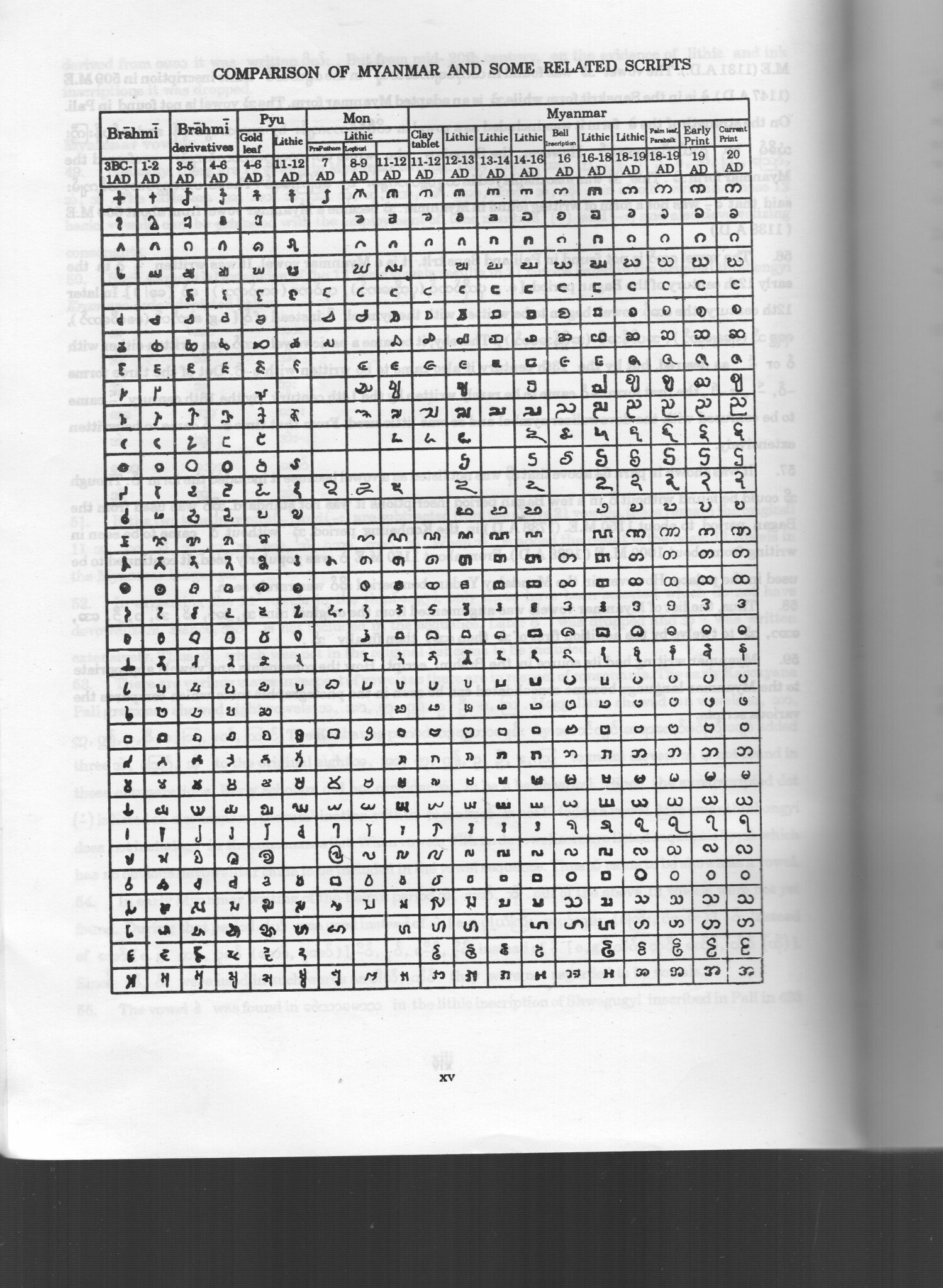

Talking about the Burmese script I want to refer to one of my teachers, Dr. Annemarie Esche, who contributed the article ‘Some problems of hybridity in the Myanmar language’ (in: Tradition and modernity in Myanmar) during an international conference in Berlin in 1993. She pointed out that the Burmese script ‘doesn’t fit’ with the language. It belongs to the group of more than one hundred ‘Indian’ alphabets that are based on the ancient Brahmi script. They are well-suited for Indo-Aryan languages. Burmese, on the other hand, is a tonal language. The same applies to Thai and other languages of SouthEast Asia. The Burmese (as well as their neighbours) came into contact with the dominant culture of India before they were able to develop an alphabet that ‘fit’ their language. And so they had to add quite a few special characters to make it ‘fit’. But problems remained.

The Burmese script has fascinated me since I saw it for the first time. Abroad it is often referred to by slightly derogatory names: ‘bubble script’, ‘pretzel script’, etc. To the untrained eye it appears as a random accumulation of circles. If you take a closer look, you will see closed and open circles. To me the script seems to be like a mirror image of the Burmese need for harmony: everything is round, hardly any corners that stick out. I’ve learnt a few Indian scripts (all based on the Brahmi script) and to me Burmese is the most beautiful one. Interestingly, there were phases in the development of the typeface when all the letters were square (see picture)!

Anyhow, the essence of the ‘pretzel script’ struck me once while I was watching a worker in the Thanboddhay Temple in Monywa (but it could have been anywhere else in the country…). He was working on a bench made of bricks that was covered with fresh plaster and his job was to inscribe it with the donor’s name. As a tool he used a short PVC pipe, which was cut off smoothly on one side (resulting in a closed circle, like our letter ‘o’). At the other end, a piece was cut out that corresponded to about a quarter of the circumference (open circle, corresponding to our letter ‘c’). The man used this tool to press the names of the donors into the still fresh plaster. I estimate that they made up about 80 percent of the text. He probably had a second pipe with him with a smaller cross-section, which he used to manage another 10 to 15 percent – fascinating! The rest then had to be engraved by hand or with special tools.