Doing legal business in socialist Burma

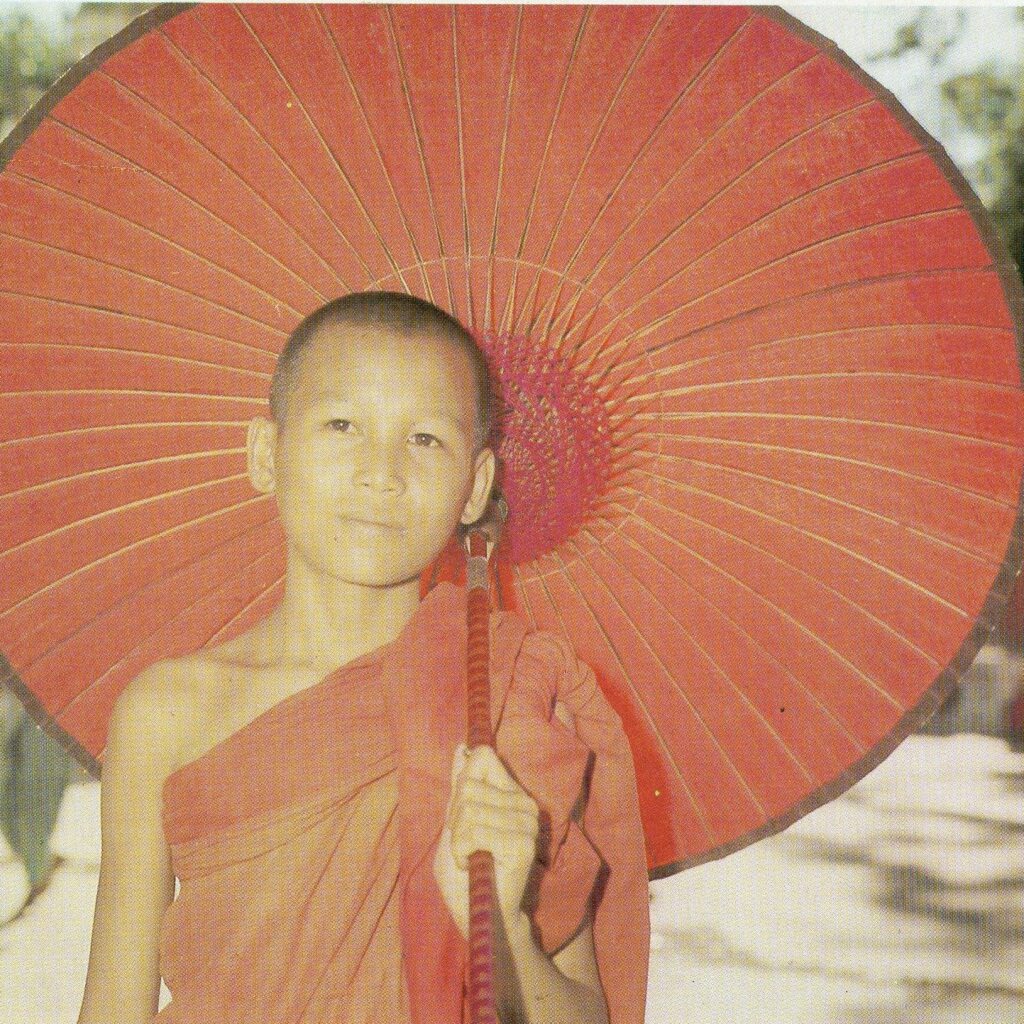

As you have read (or not?) some time ago I was involved in a lot of black market business in Burma in the 1970’s and 80’s (https://oldburmahand.com/black-market-deals-in-burma/). But please don’t think that I only did black market business. One also had to have a bit of ‘official’ business, otherwise suspicion might have arisen. So I often had the pleasure of working with MEIC (Myanmar Export Import Corp.) and Myanmar Co-Op Corp. Their catalogues were truly worth seeing; it looked like they’d been time-warped from the early 1950’s. Wish I had kept a copy … Besides marionettes (my main business) I bought things like wood carvings, mother-of-pearl items (gave me trouble at German customs), some silly souvenirs, lacquer ware, etc. Monk’s umbrellas were quite popular in West Berlin, I must have sold hundreds of them. A couple of times we sold complete Burmese orchestras with very modest profits. Now, the difficulty was that the state-owned companies had to use the official exchange rate, which was ten times higher than the black market rate. Luckily those guys were flexible and open about the rate, so I was able to solve the problem with some kind of mixed calculation. Another obstacle were the military people who were in charge of MEIC. I have had the pleasure of having to deal with them more than enough during my business dealings in Burma and I pitied the people who had to work under them. Even though their ‘superiors’ didn’t have the slightest idea about that business they tried to show that it was them who run the show. I’ve spent many hours in run-down godowns. drinking tea with these guys to keep them happy. Of course they always had extra wishes: Here a golf shirt from Thailand, there a Playboy magazine. Or Johnny Walker whisky and 555 cigarettes. Once, one of these guys showed me bird’s nests destined for Chinese buyers. They were so expensive that they were kept in a specially secured room. There were two qualities, red and white, the latter costing more.

Now you might ask yourself why the military played a role in business after all. Well, it started in the late 70s and early 80s. At that time, ‘Burmese socialism’ was standing on the brink of disaster. In the mid-1980s, the country’s official gross national product was in free fall. Agricultural production, which is so important for Burma, stagnated because the government was no longer able to import much-needed artificial fertilisers and pesticides. As early as the late 1970s, the former oil exporter Burma had become an importer of oil products for the first time in its history – despite the comparatively low level of motorization. An additional burden on the treasury that was already in deep trouble. By the end of 1987 the country’s foreign exchange holdings had fallen to $23.8 million – barely enough to fund imports for a month. On November 3, 1985, the government carried out a second ‘demonetization’ – about 25% of the money in circulation (20, 50 and 100 kyat notes) was declared invalid. Compensation was only partially paid. As a result, many people lost all their savings. The elite’s response was ‘triple grazing’.

Higher state employees, above all the army, developed mechanisms to ensure their income. In this way, officers secured additional posts in the state-controlled economy and administration – regardless of their qualifications. With these three incomes, they and their families could survive, but if one of the jobs was lost, there was a risk of social decline. This could be avoided by consistently applying the ma.lou’, ma.shou’, ma.pjou’ rule (see below). So all decisions were delegated to the top, leading to a paralysis of the entire state machine. This has not infrequently been attributed to the anade principle, but in truth it was more the structure of the state that brought about its downfall. In 1987 there was another demonetization and at the request of the government the country was included in the group of ‘least developed countries’, which eliminated part of the national debt. However, with that measure it was on a par with African countries. A severe loss of face for many proud Burmese. By 1988 the situation had become completely untenable. The result was a popular uprising that was brutally put down by the military. (Quoted after: R. TAYLOR, The State in Myanmar, p. 378 f.).

MA. LOU’, MA. SHOU’, MA.PJOU’! means: “Don’t work! Don’t get involved! Don’t get fired!” and is the motto of all government employees in the country. But also not unknown in other workplaces. Anyone who has dealt with Burmese authorities knows what I mean. On the one hand, the reasons for this are, of course, laziness, which is not surprising in view of the poor pay of civil servants. On the other it is the fear of angering one’s superiors. If you do nothing, you cannot make mistakes for which you can be held accountable. That is the general belief. Because mistakes are punished. They might even cost your life, as Myinbyushin, the lord of the white horses, found out the hard way. The legendary horseman had to deliver an important message to the king. But he didn’t make it into town before dark. He roamed through the forest for a while in order to find the city gate but did not succeed. Exhausted, he went to sleep. In the morning he was rudely woken up by soldiers: he had unwittingly pitched his camp for the night near the city wall! He was taken to the king, who ordered his immediate execution. Today he is revered as the guardian of the village (ywa saung nat). People who brought bad news to the king also had to fear for their lives. Because of these facts, Burmese are very fond of delegating responsibility. Someone gets an order and passes it on. And so does the next one. If the worst comes to the worst, the devil takes the hindmost. The main concern for the delegators is to prove that they are not at fault. This is extremely important! I cannot judge whether the ‘democratic phase’ (2010-2020) has changed anything in this behaviour. After all, the salaries as well as the pensions of civil servants increased sharply. However, the old spirit still seems to linger in the offices. Rather! My wife had high hopes that this would change after democratisation. It didn’t and she was very disappointed about it.

Let’s take a fictional example: A postman in the Magway region has his company bike stolen. Or it breaks. Since he needs it for his work, he reports to his boss in the small town and applies for a new vehicle. Of course he can’t decide that, it’s beyond his competence. So he sends the application to the capital of the region, the city of Magway. There it lands on the table of a subaltern officer, who immediately passes the hot potato on. Finally, it lies before the chief postal clerk of the province. If he ever gets it, because everyone is afraid of provoking the displeasure of their manager over this trifle. And what is he doing? Does he arrange for the man to get a new bicycle? Of course not! He forwards the matter to Naypyidaw. Where it disappears somewhere in a fascicle. The postman’s only option is to help himself. Either he steals a bike or he buys one at his own expense. Because he doesn’t want to lose his job and he can’t do it without a bike. Now that might be a bit of an exaggeration. But that’s pretty much how it works in Myanmar.

In my experience, if you make a suggestion to change existing conditions, the Burmese always see the resulting problems first. The motto seems to be best not to change anything. You hear ‘a thousand good reasons’ why something cannot work. When it comes to proposing solutions, however, they are not as creative. Myanmar is – to put it somewhat exaggeratedly – a country where almost everything is forbidden. Cycling and motorcycling are prohibited in downtown

Yangon. Rickshaws are an exception. Nevertheless, you can see many mopeds and bicycles driving around there. Hardly anyone cares if these prohibitions are violated. Neither the authorities nor the people committing the violations. Usually nothing happens. And that’s just one example. Presumably only monks can lead a law-abiding life. But then, of course, they have their own special regulations – more than 250 in all! The Burmese bureaucracy is notorious: Everything, absolutely everything, is collected, filed in folders and archived. There it rests for all eternity. But: Should the person concerned then arouse the indignation of the authorities, the old bugs come back to life and are rubbed in the nose of the ‘culprit’. This is a tried-and-tested recipe: no one can live according to the law, everyone commits violations somewhere and at some point. And if he doesn’t, you invent new laws and regulations. Or refers to regulations from the colonial era, as often happens in Myanmar.

However, during my time as shipowner I have experienced first-hand that Burmese workers are completely capable of making independent decisions. And that’s when it comes to causing damage! In doing so, they often develop amazing creativity and initiative. You don’t believe me? See here: https://oldburmahand.com/en/i-had-a-boat-veranderte-version/ OR: https://oldburmahand.com/i-had-a-boat-in-burma-deutsch/(extended version, if you read German)